A few months back, I wrote about

one problem plaguing interpretation of racial disparities in mortality rates. It isn't clear when comparing over time whether we should divide or subtract, and you almost always get different answers if you do one vs. the other.

Here's another problem facing how we interpret racial disparities.

It gets back to the difference between a fraction and a ratio - a ratio is dividing any two numbers, but for a fraction, the numerator has to be a subset of the denominator. So, miles per gallon is a ratio, but not a fraction. Dividing the number of people who vote in that town by the number of people who live there

is a fraction, because everyone who votes there also lives there. Dividing the number of people who shop at a particular store by the number of people who live in the same town the store is located in is

not a fraction, because some people who shop there don't live there. That "shopping ratio" looks a lot like a fraction, because you're dividing a target number of people by a broader baseline population, but it's technically a ratio because the numerator isn't a subset of the denominator.

In a similar fashion, race-specific mortality rates look a look like fractions, but they are actually ratios. That's because we get mortality rates by dividing the number of people counted as dying by the number of people the census counted as living at the beginning of the year. It's true that the dead are a subset of the once living, but here the issue is that the way we classify race differs between the death records and the census records.

On the census form, the head of household usually fills out the form, and describes the race/ethnicity of everyone in the household, someone that s/he knows intimately. On the other hand, death records are usually filled out either the physician certifying the death, or a mortician at a funeral home, so it is based on how someone outside the family perceives the deceased. In other words, denominator race (census) is

self-defined, while numerator race (death records) is

other-ascribed.

So, there are potentially problems where there is a large discrepancy between

self-defined and

other-ascribed race, for example, someone with Mexican ancestry who appears to strangers as White. That's how we end up with a ratio instead of a fraction: we're dividing the number of people who died with a given other-ascribed race by the number who were living with the same racial/ethnic classification, but on the basis of self-definition.

Camara Jones incorporated a question into the BRFSS that gives us a handle on the difference between self-defined and other-ascribed race: "How do other people usually classify you in this country?". Among self-identified Whites, 98% were perceived by others to be White, and 96% of self-defined Blacks were usually seen as Black by others. So far, not bad.

But only 77% of Asians said others usually saw them as Asian, 63% of Hispanics said others usually saw them as Hispanic, while 27% saw them as White, and a mere 36% of American Indians said that others usually saw them as such, even more (48%) saw them as White.

So, on that basis, we'd expect that a large proportion of Asians, Hispanics, and especially American Indians would be counted as White on the death records, which would result in lower apparent mortality rates in these groups than one might expect, and somewhat higher mortality rates for Whites than is truly the case.

And when you look at overall mortality rates, that seems to make sense: Of the major racial/ethnic groups, only Blacks appear to have higher mortality than Whites. American Indians appear to have about the same mortality as Whites, while Hispanics appear to have about 75% of the mortality rate that Whites do, and Asians appear to have about half the mortality that Whites do. But is it credible that American Indian populations have no higher mortality than Whites, or that Asians are twice as likely as Whites to live to old age?

I've been thinking about how to adjust for this problem, perhaps using the estimates from the survey data above to shift people in the denominator from the census-derived self-defined groups so that they match the other-perceived rates that the death records are based on. That's unsatisfying for two reasons: first because the classification of race on death records is other-ascribed, but it's still by someone who (ideally) has gotten to know the deceased and/or their family at least somewhat, so it's not like a random stranger passing on the street, which is closer to how the survey question is framed. Second, it makes the assumption that the death record classification is "correct" and the census data needs to be adjusted to fit the correct numerator. So, a kludgy tool, but perhaps useful.

Another way to look at this issue is to think about

where in the country the mismatch between self-defined race and other-ascribed race is likely to be greatest, then look at the mortality rate ratios across those areas. So, I figured that there wouldn't be much difference between Blacks and Whites anywhere in the country. Over 95% of both groups say they are usually seen by others as being Black or White, because there's such an extensive history of anti-Black racism in this country, and because there are very few places where Whites never see Blacks and vice-versa. But, the other three groups (Hispanics, Asians, and American Indians) are distributed very unevenly across the country, and there are many Whites who wouldn't run out of fingers before counting all the people they know from one of these groups.

So, I would expect that in places where Whites are least likely to be familiar with people of one of these groups, the level of mis-classification would be highest. And that's in fact what I saw when I crunched the numbers.

In this graph (just women for the moment), I've arranged the states from those with very few American Indians, Asians or Hispanics (like West Virginia (1.7%) and Maine (2.7%)) to those with the highest proportion of these groups (California (48%), New Mexico (54%), and Hawai'i (73%)). The colored dots indicate the apparent ratio between each groups mortality and that of Whites, the Orange dots are for American Indians relative to Whites, the purple dots for Hispanics relative to Whites, the green dots for Asians relative to Whites, and the red dots for Blacks relative to Whites.

Looking at the red dots (Blacks vs. Whites), there's not a lot of difference from one side of the graph to the other, a little increase, but not much. Not surprising because there's not a lot of misclassification of these groups.

There's also not much difference for the Asians, despite the finding from the survey research that almost a quarter of Asians report usually being seen as another race by others. It is interesting to note that the apparent racial disparity is certainly the smallest in Hawai'i, a state where API populations make up the majority of the population.

But for Hispanics and American Indians, there are really big differences depending on which side of the graph they are on. Hispanics appear to have about 70% lower mortality in West Virginia, but nearly identical mortality to Whites in New Mexico. And although the national average for mortality between American Indians and Whites appears to be about equal, in states at the lower end of the graph the mortality appears to be much lower, and on the upper part of the graph, more mixed, some higher, some lower.

Looking more specifically at Native American populations, here I've ranked the states from those with the fewest American Indians to those with the most, and this graph is spectacularly clear. Most of the states with fewer than 1% American Indians appear to have lower American Indian mortality than Whites, while all but two states with American Indian populations above 1% show higher mortality. That picture is very consistent with the idea that "others" filling out death records in states with a low proportion of American Indians are more likely to classify them as White, while the "true" racial disparity in mortality between American Indians and Whites is likely to be quite a bit higher. (the darker circle is the national average).

And arranging the states according to the proportion Hispanic also shows a very strong gradient, suggesting that the true racial disparity in mortality is a lot closer to 1 than the national average of about 25% lower.

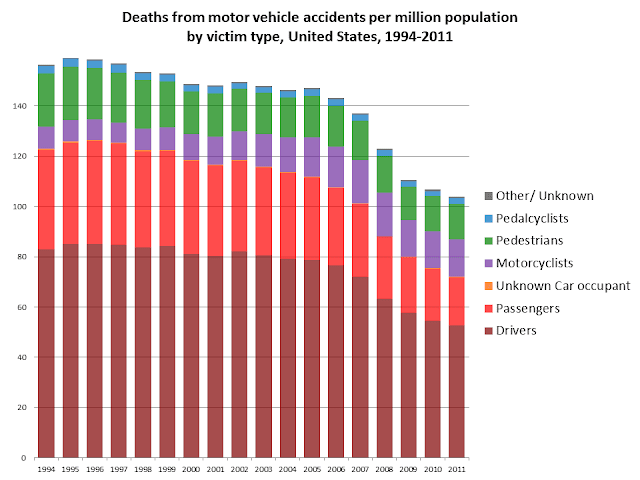

Next steps: I figure that accidental and suicidal deaths, and deaths among younger populations, are probably more prone to misclassification on the death records, because the people filling out the death certificates would have less connection to the decedent and their family, so I'd like to break these rates down that way, too.

Also, there are a bunch of datasets where they follow people up until they die, so in those cases, the numerator really does come from the denominator, so I could look in those to see what the "true" rates should be, even though these represent only a small sample of the whole population.