Turns out, the story is more complicated. The pump handle was removed long after the threat of cholera passed from that spot, John Snow had a difficult time convincing people of his theory that cholera was spread by invisible particles borne in water, and London was rocked by Cholera many times in the following decades. Yet, we should remember John Snow for being innovative, and identifying a microbial cause for cholera, an accurate description of how the disease is transmitted.

Cholera rocked London until a bunch of people (including William Farr), pursuing the wrong idea about how cholera spread, acted to protect the population at large by digging out the city streets and putting in an effective sewer system. The sewers of London were designed to cultivate a more productive working class by removing the filth that the city's "better classes" were convinced kept much of their workforce sick, caring for others, or dying before their working years had come to an end. At best, they were part right, in identifying filth. But they were very wrong in their thinking that it was harmful ethers emanating from the filth that was the problem.

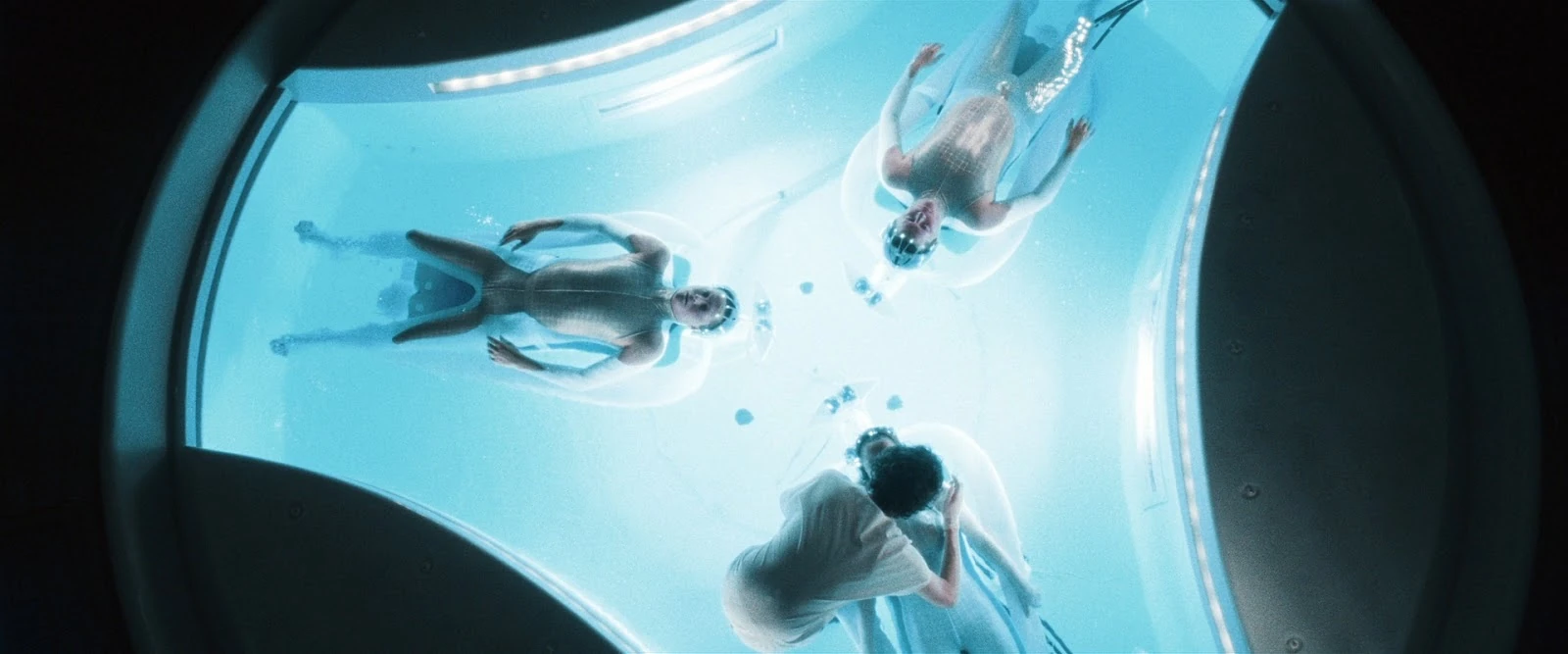

Today, the US government has committed a huge sum to the Precision Medicine Initiative, with the goal of recruiting a million Americans into a cohort, and measuring our genes, with the promise of providing individualized medical information to improve the delivery of medical care. The promise is that Precision Medicine will deliver us from the hapless poking and prodding of medical practitioners groping in the dark - to a gleaming future where, after reading our genes, a precisely-guided medication will be identified to provide us with maximal benefit. Turns out, the promise of a gleaming future where we will be known completely and our dis-eases will be readily dispatched is as old as medicine itself (see this great Atlantic post by Nathaniel Comfort).

But perhaps this time, medicine, or particularly Precision Medicine, will deliver on the promise. I would argue, that even if it does deliver miraculous rescues of many people from the clutches of truly horrifying diseases, it will likely have little impact on our health as a population, perhaps even diverting our attention from those interventions most likely to have the greatest beneficial impacts.

John Snow correctly identified the causal mechanism behind the transmission of cholera from one person to another. What he did not do (and I would argue could not do) was use that information to effectively prevent the spread of cholera from one person to another. Imagine, if you will, that he had been able to convince the authorities in London of the water-borne nature of cholera, and that it's spread could be interrupted by the timely removal of pump handles. One can imagine setting up an infrastructure to identify cases of cholera (that already existed, though could have been improved), leading to the deployment of a team of investigators to identify the probable source, and in turn remove pump handles in affected areas. Would this have stopped cholera? Yes, within days, by which time it would likely have spread to dozens of other people. And in London, a hub of global trade, the frequent re-introduction of cholera was virtually guaranteed. Not to mention the hardship on the population of having to travel farther and farther to get their water from an ever-diminishing set of functioning pumps, and whether some of those people were now carrying cholera with them to other parts of the city. John Snow and his pump handle removers would be playing whack-a-mole. They would, over the years, improve their methods and whack the cholera-laden pump handles faster and faster. But it wouldn't do anything to stop cholera from cropping up in the first place.

Installing the sewers, on the other hand, (largely) prevented cholera from being transmitted, even when it was re-introduced to the city.

My analogy then, is to whether the knowledge to be gained from the Precision Medicine Initiative (and the knowledge gained will be vast) will have much impact. The first fruits from precision medicine have been in the area of cancer treatment. Some tremendously impressive gains have been made. I imagine it's likely that many more are coming.

But the promoters of precision medicine also hold out more fantastical ideas. For instance: that we will be better able to assess the risk of future disease. That sounds awesome. If I know I'm at increased risk of heart disease, I can take action - I can eat less red meat, more veggies, exercise more, and so on. But a couple of other things also may happen that should be of great concern. The simplest concern is that people "not" at increased risk of heart disease may think they are wasting their time by doing things to prevent heart disease. Why walk laps at the mall and eat like a bird when I could just eat what I like and spare my knees the agony? But everyone is at risk of heart disease, so what's the great advantage in hair-splitting whether we are 30% likely or 70% likely to die from it?

But the promoters of precision medicine also hold out more fantastical ideas. For instance: that we will be better able to assess the risk of future disease. That sounds awesome. If I know I'm at increased risk of heart disease, I can take action - I can eat less red meat, more veggies, exercise more, and so on. But a couple of other things also may happen that should be of great concern. The simplest concern is that people "not" at increased risk of heart disease may think they are wasting their time by doing things to prevent heart disease. Why walk laps at the mall and eat like a bird when I could just eat what I like and spare my knees the agony? But everyone is at risk of heart disease, so what's the great advantage in hair-splitting whether we are 30% likely or 70% likely to die from it?What about finding out I have an elevated risk of an unpreventable health outcome? Is that knowledge worth knowing? In some cases it may be, but frankly, I'd rather not know if I have a higher risk of Parkinson's or Alzheimer's. It's just one more worry in a life full of worries. I'm glad I didn't waste time worrying about testicular cancer before I got it.

And here's a really scary thought - many of the things we do as individuals to prevent disease are ineffective - either we've got the wrong idea about how the disease works, or we have over-estimated the preventive effect of taking action, or we are taking the right action, but 10 years too late. What then are we doing to people by telling them there is a train coming down the tracks at them, then suggesting they totally change their lives, when those changes may or may not pull them off the tracks - or even worse, put them on more dangerous footing.

Individualizing risk individualizes risk

Here I think is the biggest problem, and it's where I come back to John Snow and the individualized approach to prevention. The promise of individualizing our risks - perhaps producing a scorecard with red, orange, yellow and green labels on various potential diseases facing our future selves - this individualization has an insidious impact. It implies that whatever got us to here, we ourselves are responsible for the next step. It localizes prevention to the individual, and as a result, implies we are each responsible in our own way for our health. And re-enforces the notion that others who have befallen ill health may be in some way responsible for it. Especially if we can see that they are lazy, fat, dumb, poorly kept, or even just poor. Sometimes, we just project those qualities upon them. And it takes away from focusing on steps we can take to promote everyone's health. Like sewers. Walkable neighborhoods. Shifting the subsidies for food production that would deliver all of us better options. Fewer handguns. More compassion. More connection.

I can hear some of you shouting that these goals need not be in conflict. I agree, they need not. but I'm arguing that so much of our nation's research budget, and hype about the future, are devoted to diving deeper into our genes, that leaves the rest of us a bit parched.